1.1M

Downloads

471

Episodes

SANDCAST is the first and leading beach volleyball podcast in the world. Hosts Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter take listeners into the world of the AVP, Volleyball World Beach Pro Tour and any other professional beach volleyball outlets, digging deep into the lives of the players both on and off the court as well as all of the top influencers in the game.

Episodes

Wednesday May 16, 2018

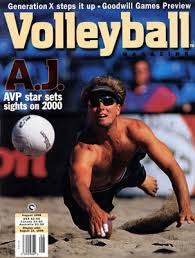

Adam Johnson: The Hall of Famer hiding in plain sight

Wednesday May 16, 2018

Wednesday May 16, 2018

Adam Johnson couldn’t believe it.

He’d had some rough losses in his day, narrow losses with a lot on the line. Twice he had been the first team out of the Olympics, and twice it was because of a random, head-scratching injury. In 1996, when Johnson was partnered with Randy Stoklos in the Olympic trials in Baltimore, the two had to win just one of their next two matches, the first of which would come against the Mikes – Mike Whitmarsh and Mike Dodd.

Thirty seconds before the match, Stoklos hit one final warm up jump serve, landed on a ball and sprained his ankle.

Johnson and Stoklos would lose the next two matches, and their bid for the Olympic Games.

Four years later, it was Johnson and Karch Kiraly, needing essentially only to qualify for one final tournament to seal their spot in the Athens Games – and then it was Kiraly who suffered an injury.

Again, Johnson was the first team out.

“Thanks for reminding me,” he said, wistfully, on SANDCAST: Beach Volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter.

Eighteen years have passed since just missing out on the 2000 Games, but stakes are still high for Johnson on the volleyball court.

Now, he’s wagering In N Out burgers.

“I’ve never lost to my girls,” he said. “Now I will say that with a little asterisk, because I am getting a little bit older, and I was up 22-10 when one of the girls shot the ball over on one and I turned to go get it and I heard my hammy go a little bit.”

Johnson wanted to call it quits.

The girls wouldn’t have it.

He made a bet: Loser takes the winner out to In N Out.

“They wanted to know when we were going,” he said, laughing. “I’m here going ‘I’m up 22-10, and you’re telling me you’re not giving me another shot?’ And they’re like ‘Well can you go right now? Or you forfeit.’ They are pretty ruthless.”

A competitive edge, perhaps, gleaned from their coach.

This was a man who, in his first full season on the beach after years playing on the indoor national team and overseas in Italy, won five tournaments and labeled that as being “kicked around.”

From 1994-1999, Johnson, playing with an armada of partners who would cement themselves as some of the best in the game – Jose Loiola, Kent Steffes, Kiraly, Tim Hovland, Stoklos – won at least four tournaments per season, in fields that were stacked with one Hall of Famer after the next.

That drive is still there.

“I don’t know if I ever gave up on being a player,” said Johnson, who retired in 2000, made a brief reemergence in 2005, before retiring again. “I’m always still trying to get up a ball up on my girls who can’t get it up, just using my foot or putting it back in play if it’s over the bench or something.

“I love coaching. I feel like I have a lot to offer. If they ask questions and want to learn, I feel like they can get better.”

Perhaps even more important: They might be able to get some In N Out.

Wednesday May 09, 2018

Adam Roberts: Beach volleyball's talent finder

Wednesday May 09, 2018

Wednesday May 09, 2018

Lay out?

Was that what Adam Roberts’ friends said? He didn’t even know what that meant. So you just walked down by the ocean, put a blanket down, and… laid there?

Nope. Not Adam Roberts, this week’s guest on SANDCAST: Beach Volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter.

His whole life, then as it is now, had been based on movement. Raised in High Point, North Carolina, Roberts grew up on a steady diet of soccer, cross country, track and basketball, receiving offers from ACC schools to run the 800 meters but also an offer from Elon College, which was just 30 miles down the road, to play point guard on its basketball team. He took the full ride to Elon, started every game in his last three years and earned All Colonial Athletic Association honors. During breaks, however, he would live at his parents’ house in South Carolina, and it was there, rather than laying out, that he discovered volleyball, a game that was quite similar to basketball in its movements – lots of quick lateral steps and explosive leaps – but it was on a beach.

So he would play pickup beach volleyball every day over the summers, and it paid off with an eight-inch increase in his vertical leap in the gap between his sophomore and junior years. In his junior season, he was leaping so high that he won four dunk contests.

“I had tried everything, man,” he said in a previous interview. “I tried the strength shoes, the SuperCat Jump Machine. It wasn’t until I began training on the sand with a weighted vest that I saw that increase, so I just used it as a cross-training sport.”

And when he graduated with a dual-degree in business and econ, Roberts was good enough that he had some small-time offers to play basketball professionally in Europe. He wasn’t interested.

“I was way too into volleyball,” he said. So he spurned the offers overseas and moved to Myrtle Beach, where his parents had built a three-bedroom house on the beach.

“I said ‘Sure I’ll live for free on the ocean and play beach volleyball,’” Roberts said, laughing. “It has a full hot tub, fire pit, a really nice volleyball court on the property on the ocean. It’s a great set up and very conducive for guys to train in.”

It didn’t take long for word to spread of the Roberts House of Volleyball in South Carolina. For nearly a decade, players cycled in and out, drinking and playing volleyball, living a life many dream of but few realize. And in the spring of 2003, when Roberts and his roommate, Matt Heath, a 6-foot-6 former collegiate soccer player turned blocker from Fort Myers, Florida, were playing in a tournament in south Florida, they happened across “a skinny white kid and a tall guy wearing steel-toed boots” that were damn good.

“That,” Roberts says, “is how I met Phil Dalhausser.”

Not long after, Dalhausser and the skinny, fiery white kid, Nick Lucena, moved to South Carolina.

They were going to become beach volleyball players.

“We would go out, I don’t know, probably on average four times a week,” Dalhausser said in a previous interview. “Adam pretty much ran the town so we’d drink for free. And those days we would roll out of bed at eleven or something like that and we’d stroll out to the courts at two.”

After the hangovers had been massaged and they were able to play, they’d head out to the court and train for a few hours and then, in between marathons of Halo, pour over film of Karch Kiraly and the greats at night.

“That house was volleyball one hundred percent of the time,” Heath said. “We’d be on a road trip discussing ‘Hey what do we do in this situation?’ It was just kind of an open forum and we just did a lot of homework on it. It was a good time. We all raised our level.”

But still, even in the Adam Roberts House of Volley, Dalhausser was different — “a freak,” Heath says, and he means it as the highest of compliments. “His improvement was meteoric, to be honest.”

When they popped in movies or played X-Box, Dalhausser would grab a volleyball and set to himself for all two hours.

“His concept was that he wanted really soft hands, almost that you couldn’t hear it coming in and out,” Roberts says. “That was his thing that he would set the ball so quietly that we could still watch the movie.”

During the winters, Dalhausser and Lucena would pick up shifts as substitute teachers and Roberts would help out with Showstopper, his parents’ dance competition production company. When it would be too cold to play on the beach, they took to the basketball courts, joining men’s leagues and dominating pickup games. And it was there – not during passing drills or watching Dalhausser set to himself during movies or winning tournaments over the summer – that Roberts knew just how limitless Dalhausser’s potential was.

“I had seen some good athletes, Division I basketball athletes, but when I saw Phil’s touch on the basketball court – he could dribble, he had a good hook shot, he could bring the ball up the court – I was like ‘Wow,’” Roberts says. “We played in a winter league, Nick is flying all over the court. I was like ‘Man he is fast. Wow, these guys, especially Phil – their potential is limitless.’

“I had always equated beach volleyball with touch. You kinda have to shoot seventy percent as a basketball player from the free throw line to be a good beach volleyball player. The reasons being, I don’t think Shaq could play beach volleyball because he couldn’t set. But Phil had this touch. He’s a different breed. Even to this day, being one of his best friends, knowing so much about him, I think you could do sports psychology just on Phil. He’s just so laid back, so chill. You read these books and stories about Tiger Woods and Michael Jordan and their whole life goal was to win a gold medal and be a world champion and MVP, and that’s not Phil.”

Dalhausser’s story is by now well-documented, as is Lucena’s. Roberts’ though, has not received the proper amount of ink. This was the man who all but discovered arguably the greatest beach player of his generation and the partner who helped get him there.

He has played in more AVP events than anyone on tour, including John Hyden. Just as he did with Dalhausser, he develops talent, sometimes traveling the world to do so, working with Marty Lorenz and Brian Cook, Brad Lawson and Eric Zaun, and now 23-year-old Spencer Sauter, a blocker out of Penn State with every indication of being a main draw mainstay.

This is what Roberts does. He plucks talent. Grooms it. Succeeds with it.

Anything but standing still.

Wednesday Apr 25, 2018

For Kelly Reeves and Brittany Howard, it's all gucci vibes

Wednesday Apr 25, 2018

Wednesday Apr 25, 2018

It would seem that Kelly Reeves and Brittany Howard have been playing together for years. At the very least, it would seem as if they’ve been close for quite some time. They smile constantly. Laugh even more.

On more than one occasion on SANDCAST: Beach Volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter, one finished the other’s sentence or filled in a blank.

Little about their natural chemistry, which is evident both on a volleyball court and in a podcast studio, suggests that the two have only recently begun a partnership and, by extension, deepening a friendship.

And yet here they are, exactly two tournaments in, complete with two bronze medals in a pair of NORCECA events, in Aguascalientes and La Paz, respectively, with a main draw just one week away for FIVB Huntington Beach.

For Reeves, this is no longer a novel concept, to pick up with a new partner and enjoy immediate success. She’s done this at every level of her career. Doesn’t matter if it was at Cathedral Catholic High School, where she won four straight CIF titles and graduated as the all-time kills and digs leader in San Diego County.

“I think that’s been passed,” she said, laughing.

She one-upped herself at UCLA, winning a national championship indoors in 2011 –- technically, she was also a member of the 1991 national championship winning team, rooting on the Bruins from the womb as her mother, Jeanne, was an assistant coach -- before hitting the beach and becoming the first UCLA All-American on the sand.

The AVP was no different, either. Reeves’ career began in 2016, in Huntington Beach, and a fifth-place finish with Ali McColloch assured her that she wouldn’t have to grind through an AVP qualifier again. She was named rookie of the year, and a year later, partnered with Jen Fopma, she reached the semifinals twice.

Two events into the 2018 season, she’s matched that total, with a partner who is a bit stunned herself by the pair’s quick success.

“A year ago, if you would have told me this is where I would be, that I’d be partnered with Kelly Reeves, playing in a NORCECA, I would definitely not believe you,” Howard said. “It’s just been really cool and awesome experience.”

A year ago, Howard had no plans to play AVP at all. After graduating from Stanford with a degree in Science, Technology and Society, Howard had a job offer in El Segundo. She planned to take it, maybe play in a few CBVAs. Nothing more, save for maybe the occasional local AVP tournament.

But Corinne Quiggle, her partner at Pepperdine, where Howard competed for a fifth year as a grad student, asked if Howard might want to play a few, beginning with New York in early June. They had just come off a third place finish at the USAV Collegiate Beach Championships, pushing USC’s indomitable duo of Sara Hughes and Kelly Claes to three sets.

Why not?

So off to New York they went –- and lost in the first round of the qualifier. Then to Seattle with the same result. San Francisco saw a second-round exit before a breakthrough in Hermosa and Manhattan Beach, where they coasted through both qualifiers in straight sets.

By season’s end, Howard, who had no plans to play on the AVP Tour, was a three-time main-draw player, a stunningly fast learning curve from a girl who readily admits she had a “rough start” to the beach at Pepperdine.

The rough start is firmly in the rearview, as Howard, technically still a rookie, is now partnered with one of the most athletic defenders on Tour, taking thirds in NORCECAs, enjoying champagne showers before the season has really even begun.

“We definitely celebrated on the podium for sure,” Reeves said, laughing. “That was my first time doing the champagne and I just sent it. Full send … It was our last pair of nice clothes and we were just drenched in champagne.”

A good problem to have.

Or, rather, as the ever-affable Reeves is prone to saying: A “Gucci” problem to have.

Wednesday Apr 18, 2018

Jose Loiola's legend only continues to grow

Wednesday Apr 18, 2018

Wednesday Apr 18, 2018

To read through the old LA Times archives, to dig through all of the gushing, flattering pieces, is to remember Jose Loiola as a man of near mythical proportions, a beach volleyball Paul Bunyan. How hard he could hit! How high he could jump! How entertaining he was to watch! How loud and brash and charismatic he was!

Loiola laughs at those memories. He laughs through a glass of wine, even though he has sworn off alcohol during the week.

It’s just one glass, right?

Nothing compared to what he and the boys could put down during the 90s, when the AVP was a rollicking party dishing out tens of millions per year and Brazil was in its nascent stages of becoming a bona fide beach volleyball power.

Loiola was the first, and for the 48-year-old there is no forgetting the day he and Eduardo Bacil took down the Gods. Back then, in the late 80s and early 90s, the Gods were known as Smith and Stoklos.

In the 86, 87 and 88 seasons, Sinjin Smith and Randy Stoklos would win 44 of 71 AVP tournaments and three of four FIVBs. You could count on one hand the teams who had a shot at beating them, and Jose Loiola would not have been among them.

It is with a delicious stroke of irony that Loiola and Bacil, a fellow Brazilian, stunned the Americans in their primes. Beach volleyball had been a weekend activity in Brazil prior to 1987. Nothing more. It was a soccer-mad state with beautiful beaches and recreational volleyball.

It was Smith who had a vision for the sport to grow internationally, Smith who worked with then-FIVB president Ruben Acosta to grow the game overseas, Smith who helped form an exhibition match in Rio de Janeiro, awakening the dormant beach volleyball giant that is the nation of Brazil.

Without Smith’s and Acosta’s efforts to establish the game in Brazil when they did, it’s quite possible we might never have heard of Loiola and Bacil. Without the FIVB establishing a beach volleyball branch to its indoor league, there may not be beach volleyball in the Olympic Games, and by extension no reason for Americans to pay attention to Brazilian beach volleyball at all.

But in 1993 there was no longer a choice. They had to watch, and with rapt attention, as Loiola and Bacil, who earned a wildcard to a pair of AVP events, in Fort Myers and Pensacola to begin the season, and then made every main draw after that on points, established themselves as one of the only international teams who could be reasonably expected to beat the Americans.

“I had the opportunity to play with and against the players I had grown up idolizing, the players I had grown up watching,” Loiola said on SANDCAST. “To me, that was the best thing. I’m competing with them and I’m beating all of them. From that point on, I realized if I put my time in and I become more professional and learn the hoopty-hoops, with the discipline and the perseverance, I knew I was going to get far.”

Loiola is not a man prone for understatement, and yet for him to describe his career as able to go far, and not to distances never before seen by a Brazilian beach volleyball player, is an understatement indeed. For at the end of that 1993 season, Loiola had been awarded the AVP Rookie of the Year, the first international player to do so.

In ’95, playing in an indoor beach tournament in Washington D.C., he and Bacil beat Stoklos and Adam Johnson in the finals, marking the first time an international team had claimed an AVP title.

“The AVP was the NBA of volleyball,” Loiola said. “It attracted the best players on the planet. It was, by far, the best tour.”

So much so that the AVP’s status as the premiere tour began to create animosity both in the U.S. and elsewhere. The Brazilian federation wanted Loiola to quit playing on the AVP and join the Brazilian national team so he could represent his native country in the 1996 Olympics, its inaugural year as an Olympic sport. The Americans, meanwhile, fought over a similar fault line: Why would they compete on the FIVB, an inferior tour with inferior money, to qualify for the Olympics? What could possibly compel them to travel overseas to play in a tournament for less prize money, against teams that couldn’t compete on the AVP, rather than stay home and play against the best?

While the Americans fought for a U.S.-based Olympic trial, Loiola demurred. He wasn’t going home to compete for a Brazil on the FIVB. He didn’t care about the Olympics. He cared about playing against the best.

And in those halcyon days, the AVP featured the best.

“In 1996, I had the choice,” Loiola said. “Either I go to the Olympics or I stay here and play AVP. I didn’t go to the Olympics. Why would I want to go to the Olympics when I could stay here, play 25 or 26 tournaments, making three times more money, why would I want to go to the FIVB and travel all over the world?”

He didn’t, choosing to remain in America while Brazil sent Emanuel Rego and Ze Marco de Melo and Roberto Lopes and Franco Neto to Atlanta. Neither finished better than ninth.

Loiola had no real reason to change course. Named the AVP Offensive Player of the Year from 1995-1998, he was one of the best players in the world playing on the best tour, with the top competition and more prize money than the sport had ever seen.

And then the AVP tanked.

Years of financial mismanagement had been masked by packed stadiums and electrifying volleyball and a rabid fan base. In 1997, the façade crumbled.

The AVP went bankrupt. The script had been flipped. To the FIVB Loiola went, rising up the world rankings with Rego, winning the FIVB World Championships in 1999, holding the No. 1 ranking heading into the 2000 Olympics, in Sydney, only to succumb in a stunning upset, finishing ninth.

“We just had a bad game,” Loiola said. “No excuses. Sometimes that just happens.”

It is one of the great shames of the sport that beach volleyball success is measured by Olympic success, for Loiola would never return to the Games. His hips went bed, to the point that he said he “was playing on one leg.”

His final event came in 2009, in Atlanta with Larry Witt. He’s since been inducted into the CBVA Hall of Fame, the International Volleyball Hall of Fame, the Volleyball Hall of Fame.

A living legend. And one who’s now imparting his wisdom on the next generation of them, serving as the coach of Sara Hughes and Summer Ross.

The fire’s still burning, the embers still hot, even as a coach. So disappointed was he after Hughes and then-partner Kelly Claes finished ninth in Fort Lauderdale that he hopped on the first flight out.

Now it’s Hughes and Ross.

He loves Hughes’ fire, Ross’ spunk. He wants to win FIVB Huntington Beach in the first week of May, knowing how much it would mean to Hughes, a Huntington native.

“That’s the one we want to win,” Loiola said. “In our home, our homeland. We’re excited, we’re on the right track. It’s just a matter of time.”

Wednesday Apr 11, 2018

'Weird-athletic, scrappy twig-noodle' Witt sisters prepared for rookie seasons

Wednesday Apr 11, 2018

Wednesday Apr 11, 2018

Don’t let these Witts fool you, with their Colgate smiles and constant giggles and impossibly amiable personalities.

Then again, how could you not be fooled?

Was that McKenna in the Oakleys or Madison? Wasn’t McKenna on the right? Or did they switch?

Hold on…it was Madison with the 4-centimeter tear in her ab…right? Or was that the other one, the one who looks just like her, down to the cascade of dirty blonde hair and almond-shaped eyes and what they call “twig-noodle” frames?

Kerri Walsh couldn’t figure it out when she played the Witts in 2016. Neither could their high school teachers on the one occasion they swapped places in math and Spanish, though so overwhelming was their guilt and nerves that they never did it again.

“I was so nervous,” McKenna Witt, now McKenna Thibodeau, said.

Yes, the Witt sisters are technically no longer. McKenna is now a Thibodeau, and Madison, recently engaged, will soon become a Willis.

The Thibodeau-Willis sisters don’t exactly have the same ring as the Witt Sisters. No matter. They still have the same identical looks, despite an NVL official once attempting to change that, marking Madison with a No. 1.

Or hold on. Was that McKenna?

Not that it mattered. She washed it off anyway. McKenna had a tear in her ab, and she wasn’t going to be picked on. Beyond that, Madison wasn’t going to let another team complain about playing a pair of identical twins, especially when one of them is injured, and exposing which one that was could mean furthering the injury.

Simply put: You don’t mess with a Witt, and you certainly don’t mess with one when the other is on the same court.

“We’re fierce competitors,” Madison said,. Killers with a smile.

So hungry for success are they that in less than five years playing beach volleyball they’ve become All-Americans, finished their four years at Arizona with an 85-33 record, qualified for an AVP in San Francisco in 2016, grinded through an NVL qualifier in 2017 and advanced to the semifinals, picked up their Masters degrees doing a grad year indoors with Cal Baptist all the while planning McKenna’s wedding.

Now they’re the poster girls for P1440, selected as one of the tour’s developmental teams.

It appears to have been a smooth ride for the Witts. Little turbulence, few setbacks, the American Dream from a pair of sisters who are as likable as they are marketable. Their path has been quite the contrary, and they like it that way.

They love telling the story about how they were cut from their seventh-grade team, touching a ball for the first time in an organized setting in eighth grade. They aren’t necessarily enamored with their 13-15 record at Arizona as freshmen, but they’re able to look back upon it with fondness, for prior to the season, they had to relearn how to throw a ball, let alone hit one. They’re not kidding, either. Their coach, Steve Walker, didn’t like how they threw a ball, which replicates the mechanics for an arm swing. So in their first week as collegiate beach volleyball players...they threw volleyballs.

“Looking back, we loved the process,” Madison said. “Steve would always say ‘Rome isn’t built in a day’ and man is that true… The process is beautiful. You don’t grow on mountaintops.”

They didn’t. And their steep growth created a style they refer to as “scrappy, weird athletic, and fun.”

The weird athletic can be up for interpretation. The fun part is not. They’re contagious, these Witts, forever smiling, laughter providing the soundtrack to their conversations, humble from an upbringing ground in faith.

“We’ll do whatever is takes to win,” McKenna said. “But we’ll still be nice.”

Wednesday Apr 04, 2018

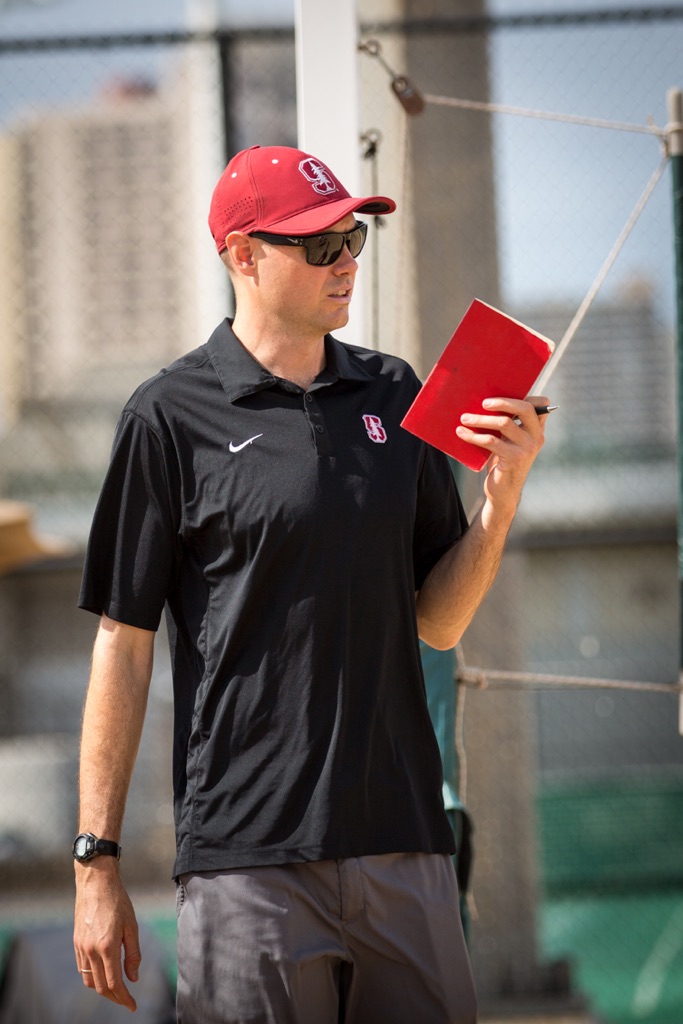

Stanford beach volleyball continues to strive for more, with Andrew Fuller

Wednesday Apr 04, 2018

Wednesday Apr 04, 2018

Stanford beach volleyball is, in one aspect at least, no different than any other athletic team in that every member has their role. Like, say, the player whose job it is to remind everyone of their inevitable mortality, and that all things should be taken in perspective.

Or the one who brings in studies on the positive impact of placebo effects.

Or the researcher who is studying the physiological effects of forgiveness.

Or the yoga instructor. Or the Olympic assistant coach.

Or the sports psychologist, who “does sessions with the team that are very different,” coach Andrew Fuller said on SANDCAST: Beach Volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter. “We’re inserting different voices and perspectives and voices into their world, because you never know what’s going to stick… People at the national level don’t have this type of support.”

Welcome to Stanford, the most academically rigorous and, almost paradoxically so, one of the most athletically competitive universities in the country, with the resources and exceptional minds to prove it.

“One of the things that really excites me about being at Stanford is not only the abundance of resources but the level of access to the resources and I would be remiss if I was not taking advantage of people who aren’t just easily accessible but are super stoked on what’s happening in athletics and want to help out,” Fuller said. “I think there’s a particular irreverence to Stanford that I enjoy.”

That unique level of expectations, that irreverence, is as much an advantage as it is a challenge. Some schools, like LSU, for example, are limited geographically. Stanford’s excellence, and its demands to continue to be excellent, are, ironically, its biggest hurdle.

This year, 47,450 students applied to Stanford. Only 2,040 were admitted – 4.2 percent, the lowest acceptance rate in the country, ever.

“It’s very self-selecting, and we can have some conversations that are very brief,” Fuller said. “We can have a conversation with a young student-athlete who, athletically, is wonderful, and is perhaps a very good cultural fit for us. And then we see the transcript and the conversation just stops. Stanford’s a choice, and some students don’t want to do the work that is required to get there. It’s my belief that for some students, Stanford is worth the work. And is it going to be easy? Not at all. It’s going to be difficult. And people who are up to that challenge and go through it thrive at Stanford.”

Indeed. One in particular, a name volleyball fans are likely to become familiar with in the years to come, is Kathryn Plummer, Stanford’s 6-foot-6 sophomore who already owns a lengthy list of accolades – Pac-12 Freshman of the Year on the beach, the ESPN W Player of the Year indoors among them.

“She’s doing things from a technical standpoint we haven’t really seen in players her size, ever,” Fuller said. “If any listeners get to watch her, KP is hand setting every ball that she can. If she can get her hands on it, she will. I’m trying to remember the last player her size who has ever hand set. I would love it if someone could name someone who’s 6-foot-6 who’s saucing. She’s kind of breaking the history of someone what it means to be a tall player… The approach she’s taking and the chance she’s taking and the risk – those are the things I’m stoked about, the way she’s approaching the future of her game.”

Plummer is exceptional, yes. But her mind, her approach, is also befitting the Stanford culture – the top one percent of the one percent.

“I’ve learned that if I don’t have a damn good reason for doing something, they’re going to find the holes in it and just blow me up,” Fuller said, laughing. “That’s the greatest gift. Whether that’s some game or drill that I come up with, they’ll immediately pounce on the loophole of it and sometimes I’m like ‘You guys are right.’ They just crush me all the time. What’s that old adage? Surround yourself with people who are better than you? At any point, I am the dumbest person in the room.”

The dumbest person with a bachelor’s degree from Virginia Tech and an MFA from the Academy of Art in San Francisco, who also happened to have a fair volleyball career of his own.

Not a bad option to have for a head coach.

Wednesday Mar 28, 2018

LSU coach Russell Brock on building a beach power...without a beach

Wednesday Mar 28, 2018

Wednesday Mar 28, 2018

A common issue being navigated by the vast majority of college beach volleyball coaches: “What tools did they have in their indoor game?” LSU coach Russell Brock said. "Being able to evaluate them on film or in person, to be able to say ‘You know what, this is the stuff that’s going to translate really well to our game, or these are the things that are going to limit our ability to be successful on the short term.’ It’s gotta be a fast transition.

“What do they do well and how can I help them understand how it can directly translate to the beach game?”

Whether it’s LSU or USC or Pepperdine or UCLA, nearly every college beach coach will have to make that evaluation – how much of a player’s game will have to be modified from indoor to fit the sand?

Brock, though, and every other sand program not located on one coast or another, has another obstacle: How do you get volleyball players to play beach volleyball for a school that is nowhere near a beach?

LSU is located in Baton Rouge, a good four hour drive from Gulf Shores, Alabama, site of the NCAA Championships and likely the closest natural beach there is for the Tigers. It presents an obvious dichotomy from, say, USC, UCLA, Pepperdine, Hawaii, Long Beach State, Cal Poly, Loyola Marymount and a number of other programs that have a bounty of beaches to choose from.

Manhattan Beach or Hermosa? Santa Monica or Huntington?

LSU plays at a bar.

Ok. That sentence is misleading. Yes, Mango’s Beach Volleyball is a bar and restaurant, but it also comes equipped with 13 beach volleyball courts that are well-lit, well-maintained and as deep, if not deeper, than Manhattan Beach’s famously deep sand.

It is, objectively speaking, an excellent complex, one that prides itself on being the home of LSU beach volleyball.

But it’s not a beach. While as close a representation as a sand complex can get, Brock recognizes that the location of California alone is “just a massive advantage from a recruiting perspective,” he said. “And I went to [U]SC, so I understand the passion that’s involved with the tradition of all the schools out there with UCLA and Long Beach, and the girls who have wanted to go there growing up because their parents played and their grandparents played and it’s what they just do. Inevitably there’s a big advantage to that.

“The realistic perspective is, a lot of those players aren’t interested in leaving California, and I get it. I don’t hold it against them, it’s a beautiful place. There’s a ton of opportunities to play a sport at a really high level out there. For us, it’s about building our brand as a beach program to prove that we can play the game and play it well, to become attractive to people, regardless of where they’re from, to respect it and to know that we can train them and we can give them opportunities moving forward to continue to play the game and compete at the highest level. And that’s what takes time.”

But not, it seems, a tremendous amount of time. LSU is already one of the top programs in the country, consistently in the top 10 of the AVCA coaches poll, beginning the season at No. 6.

“We’re looking for the very best talent, wherever it might be,” Brock said. “We can’t care where they come from… and LSU is a pretty unique place. When people do move here from wherever they come from, they’re always impressed. There’s a lot of things that if you want it, we can provide it, and we can provide it at a super high level.”

Wednesday Mar 21, 2018

Maddison McKibbin and the making of the Beard Bros

Wednesday Mar 21, 2018

Wednesday Mar 21, 2018

The McKibbins are not all that different from any other set of siblings, if not a touch more hirsute and athletically inclined.

They fight. They argue. They point out one another’s flaws, sometimes a bit gleefully. And they do this often. Often enough for Riley McKibbin to film a video blog detailing the frustrations of volleyball, and playing volleyball with your brother, and how to deal with these frustrations.

“I think we would both agree that we have a hard time listening to each other,” Maddison McKibbin said on SANDCAST: Beach Volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter. “Just because you’re brothers, if you hear one word of critique, you go straight back to the last thing he messed up on, and you’re thinking ‘Dude don’t talk to me when you’re doing this.’ You revert to it and it’s so bad. I would never treat anyone else like that.

“It’s this battle of trying to take suggestions and criticisms and critiques constructively and I know that sounds very basic but it’s hard when it’s your brother.”

Their relationship is at once their biggest strength and vulnerability. On a tip from defender Geena Urango, a fellow USC Trojan, the McKibbins now pick out three aspects or skills each of them want to work on in practice, which has both improved their volleyball and reduced the resistance to critiques from a sibling.

“If we mess up on something else, it’s ‘I’m not going to get mad at you, you’re not going to get mad at me, we’re just working on these three things,’” Maddison said. “And then enforcing at the end of practice one thing that went well and one thing that we’re working on. The idea is to cut down on the frustration and whatever you want to call it between you and your partner, because when you have a plan, you can call someone out if you really want to, like ‘Hey, Riley, you suck at number two.’”

It’s why this past season was so different for Maddison, who hadn’t played with anyone aside from Riley since 2011. When Riley hurt his hand in the season-opening event in Huntington Beach, Maddison was forced to explore partner options, to play with someone he didn’t share a childhood with, didn’t share the USC court with, didn’t travel throughout Europe with, didn’t grind through the qualifiers with.

What he found was this: Finding, and keeping, partners, is tough. Meshing with new partners is tough.

Playing without your brother is kinda weird.

He played Austin and New York with Reid Priddy, and in the subsequent shuffle prior to Seattle, he wound up with Ty Loomis. And after getting swept out of Seattle, they stunned no small number of people in winning San Francisco just two weeks later.

Most would have thought Maddison and Loomis would stick together. A no-brainer. They were champs!

Then again, most don’t understand the bond between the Beard Brothers.

“When I played with Reid I told him ‘When Riley’s coming back, I’m playing with Riley’ and it was the same thing I told to Ty,” Maddison said. “And Ty wanted to keep going and I completely understand. But to me, I’m an incredibly loyal person, and I love the game of beach volleyball, but we both know that, financially, it’s hard to sustain, and playing with my brother, I love playing with my brother.

“When we win, it’s that much better, and when we lose, it sucks. In order to make this lifestyle sustainable, we have to create content, we have to develop a brand within the sport, and I’m not saying I’m only playing with him because of our brand, but when you win with someone who’s had your back for that long, or has encouraged you to pursue so many different things, that in itself is enough to say that ‘I know I had success with this one person but I’d much rather win with you.’

So my goal is: ‘I want to win with you. I want to be these idiotic beard brothers on the AVP. That’s where I want to be in life.”

Monday Mar 19, 2018

Newcomers highlight first Norceca of the beach volleyball season

Monday Mar 19, 2018

Monday Mar 19, 2018

Troy Field was, in his own words, “terrified.”

“Just so scared to mess up,” he said on SANDCAST: Beach Volleyball with Tri Bourne and Travis Mewhirter, “to, you know, disappoint this incredible athlete.”

It helped, then, that the incredible athlete in question during last week’s Norceca qualifier was Reid Priddy, and few in volleyball understand what Field was going through more than Priddy. He’s been to four Olympics. He’s won a gold medal. He’s won a bronze medal. In just a single year on the beach, he was one point away from making a final, in San Francisco.

“He’s got some pretty amazing wisdom to offer,” Field said.

Priddy told the 24-year-old that nerves are good. Nerves mean you’re excited, that you care. Focus on what you can control. Not passing or setting or swinging or serving. Just breathing. Which is exactly what Field did.

“I’d see him take a deep breath, which reminded me to take a deep breath,” Field said. Simple. And effective.

Priddy and Field opened with a three-set win over Adam Roberts and another up-and-comer, Spencer Sauter, which put them into the de facto finals – two teams come out of a Norceca qualifier, so the actual final match is of little consequence – against 2017 AVP Rookie of the Year Eric Zaun and veteran blocker Ed Ratledge.

“It was just high level volleyball,” Field said. “Just side out after side out after side out. We battled, battled, battled and took the first set like 27-25. With all that momentum, we were able to figure out what they were doing and Zaun wasn’t really hitting any balls and we were able to work our defense around that and we ended up winning like 21-16 or 21-15 or something like that… Reid was playing out of his mind, just making unbelievable defensive plays.”

It didn’t much matter that the two would lose the next match against Avery Drost and Chase Frishman. They were in, earning spots into a series of tournaments, two of which will be in Mexico, the final in Cuba.

Those three tournaments, should the two choose to play in all of them – they are more than likely not, as the Cuba tournament will run too close to AVP/FIVB Huntington Beach in the first week of May – would add up to one more professional tournament than Field has played in his career. In 2017, he played in a pair of AVPs, failing to make it out of the Hermosa Beach qualifier before making it through in Manhattan Beach with Puerto Rican Orlando Irizarry.

“It’s pretty unreal,” he said. “I’ve never been the person to get super overly excited because I feel like the more you build it up you’ll get disappointed. Everyone has been telling me to just enjoy the moment.”

On the women’s side, another newcomer, Brittany Howard, earned a bid as well. There’s a better chance you’ve heard of Howard than Field. She competed for four years indoors at Stanford before doing a grad year on the beach for Pepperdine, though she was so rusty on the beach that she admitted to DiG Magazine that “I was terrible.”

It’s become apparent she’s a quick learner. Playing with Kelly Reeves, the 2016 AVP Rookie of the Year, Howard beat Amanda Dowdy and Irene Pollock and then the new partnership of top-seeded Kelley Larsen and Emily Stockman, earning their Norceca bid despite also losing the final match to Kim Smith and Mackenzie Ponnet.

“I definitely kind of explored my options,” Reeves said on SANDCAST. “Brittany Howard was always someone I’d been watching from afar and I told her I’d love to get in the sand and try it out. We did and it just felt super comfortable, I don’t know, the chemistry thing was big. We’re definitely volleyball people and I definitely understood where she was as far as up-and-coming. Just the first time we stepped in the sand it was ‘Oh, this girl, she’s got some game.’”

Game enough to have qualified for the final three events of the AVP season, in Hermosa Beach, Manhattan Beach and Chicago, respectively. Game enough to have actually beaten Reeves in Manhattan Beach.

Game enough to have found her new partner for the 2018 season.

Reeves played the majority of the 2017 season with Jen Fopma, though with Fopma pregnant, she had to find either a new blocker or a scrappy defender to play with in 2018. Enter Howard.

“She just did some really funky stuff like ‘Ok I can work with that,’” Reeves recalled when she played Howard. “And then looking to next year, knowing Jen was out, I was like ‘Alright she’s definitely someone I would want to play with.' As soon as we got in the sand, there was just this one play, she had this nice scoop, maybe a block pull move, and she dug it and I set her and she just crushed this ball and I was like ‘Ok she’s got some game.’”

They proved as much last week, and now they’ll be taking two trips to Mexico though the third stop, in Cuba, is unlikely, for the same reasons as Field and Priddy will likely be skipping as well. There’s Huntington, with more to prove, more to learn, a bigger platform on which to play.

“We’re both still new to the game,” Reeves said. “Grantred this is my third season but I’m still learning a ton and she’s still learning a ton and it’s fun to learn and grow with someone. We’re hungry and eager to just get better and I think that’s something I really like about our partnership.”

Wednesday Mar 14, 2018

Brotherly love with Maddison McKibbin

Wednesday Mar 14, 2018

Wednesday Mar 14, 2018

Maddison McKibbin was finished.

Finished with volleyball. Finished with being overseas. Finished with not being paid. Finished with the shady ownership of international volleyball teams. Finished with it all.

He had played the game long enough, beginning at Hawaii’s famed Outrigger Canoe Club then onto Punahou School, where he became a three-time state champ, which preceded four years at USC, where he made a pair of Final Four appearances.

And now there he was, in Greece, looking at his bed, where a random Brazilian man was laying, fast asleep.

Evidently, the owner of McKibbin’s team had signed a new outside hitter. He didn’t tell McKibbin, though apparently he did give the new Brazilian outside the keys to the apartment.

That was it. McKibbin was out. He was going home. Was going to finish his Master’s Degree. Was getting out of volleyball.

Time for something else.

Riley McKibbin, Maddison’s older brother of two years, had other plans. He was going to play in Italy. Would Maddison want to come, just to kick it for three months, drink some wine and hang out in Italy?

For that, sure, he could delay grad school for a few months to hang in Italy. So long as he wasn’t playing volleyball, he was in. And then Riley had another idea.

“What if we give beach a try?”

They had the talent. There was no questioning that. They had been raised in uber-competitive Hawaii, alongside Taylor and Trevor Crabb, Spencer McLaughlin, Brad Lawson, Tri Bourne, competing occasionally against AVP legends Stein Metzger and Kevin Wong and Mike Lambert. Both of the McKibbins had played in FIVB Youth tournaments, and they proved they were good enough indoors to compete and make a living at a professional level.

The transition from indoor to beach sounds simple enough. It's a similar game with similar skillsets, where the underlying principle is the same: pass, set, hit. It, of course, was not. They weren’t entirely sure what the state of their beach skills was, so they bought a handful of AVP volleyballs from Costco and exiled themselves to a court in Venice Beach, a few zip codes away from any serious players. And so there it was that you could find two professional volleyball players, practicing in Venice Beach, legitimately mortified that someone might see them dusting off the rust of a game they hadn’t played for the better part of a decade.

“We couldn’t even hit it over the net,” Riley said in an earlier interview. “The transition from indoor to the beach is so hard. We’re both indoor players, and making that switch is a lot harder than people think.”

Unless, of course, you’re the McKibbins. In the first qualifier they entered, not long after scraping the rust off their beach games, in New York City in 2015, they qualified.

And thus the Beard Bros were born.

Their relationship is both like that of any other siblings – fighting and squabbling wrapped in brotherly love – and yet it is also nothing like that of any other siblings. The McKibbins are partners in everything they do. They’re roommates. They’re business partners. They're AVP partners. They shoot the wildly popular McKibbin Volleyball videos together. They vlog together. They play together.

Even when Maddison won AVP San Francisco while Riley sat out with an injury, even when he was fielding calls from Reid Priddy, even when he had no shortage of partner options, there was never any question whom he would be playing with: Riley McKibbin.

“Riley,” he said on SANDCAST, “is the reason I’m playing volleyball right now.”

And so it is that Maddison, so long as Riley is healthy, will not play with another who's last name is not McKibbin. They're a package deal. Whether they're vlogging about the frustrations of volleyball, filming a tutorial from Kelly Reeves on the nuances of bumpsetting, or practicing against Sean Rosenthal and Chase Budinger, they're going to do it together.

The only thing, for now, that it seems isn't on their agenda?

Shaving.